Loss of Capital

6 ways our investments can face (semi-)permanent loss

(I started drafting this post before the news on the SIVB collapse came through. I decided to postpone my post in order to collect my thoughts a little bit more.)

As long term investors in the Coffee Can style of investing, we don’t trade in and out of positions. We tend to either accumulate or maintain positions. The assumption is that we don’t lock ourselves out of an opportunity to make money in the long term, by chasing the vagaries of the short term.

If that is indeed the goal, then one of the key elements of Coffee Can investing is to prevent loss of capital, either permanently or semi-permanently, while we hold the slice of businesses we are invested in. If we can do so, then the upside should take care of itself.

Given that objective, it is important for us to understand the avenues of (semi-)permanent losses of capital, so we hopefully avoid them. In this post, I list what I think are the avenues:

Bankruptcy/Insolvency

This is the simplest of all of the avenues for you to lose money in a stock investment. The company turns out to be insolvent one fine morning/evening/night. Sometimes the symptoms show up sooner, but many times it won’t. When it happens, you are likely down and out on that investment.

Signs of something amiss in the company might be there, but unless you are an exceptionally good investigator of the company (and I don’t profess to being one), then there is a good chance you may not spot it.

Examples: Lehman Brothers, Silicon Valley Bank1

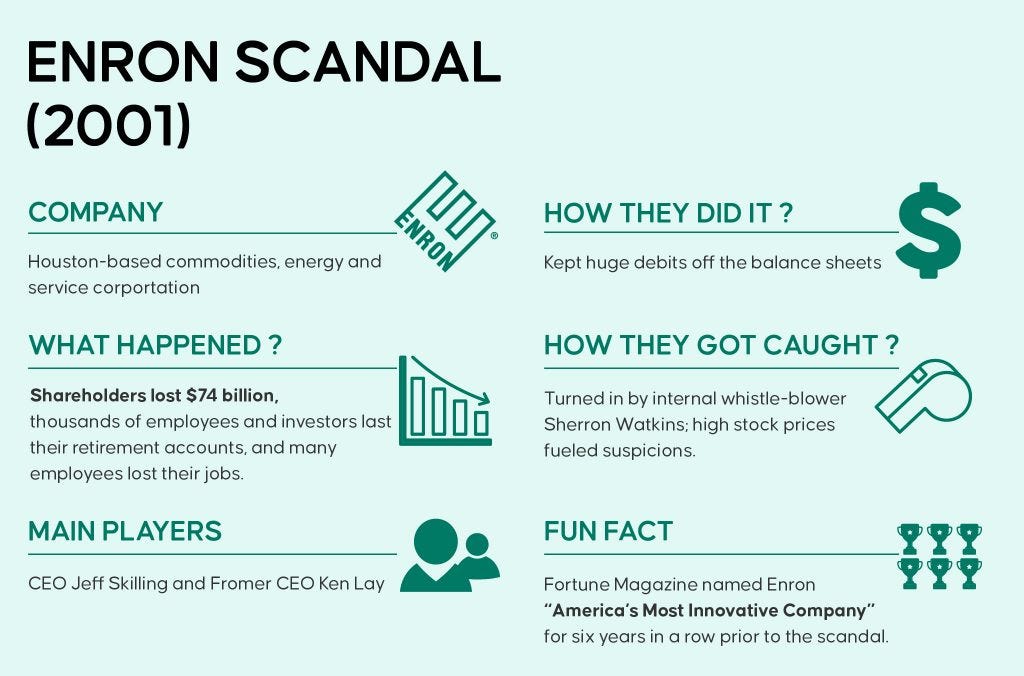

Fraud

One fine morning you might wake up to realise the company had been lying about the business, either in subtle ways, or in a blatant manner, and when the issue eventually bubbles up, there is nothing much left for the company to go on. The business collapses, investors lose their money.

(This case differentiates itself from the former case in that if the management hadn’t lied, there is always a distinct possibility the business would have carried on, but by lying they prevent themselves from taking the steps needed to fix the business.)

Examples: Enron, Worldcom, Satyam, Patisserie Valerie etc

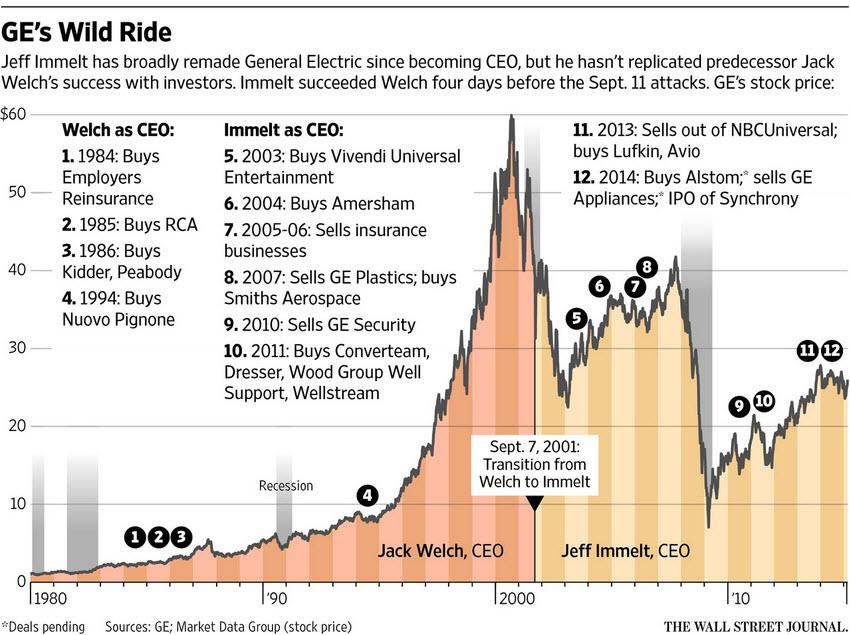

Degradation / Rerating of the business

Some changes in the society, or the ecosystem might change, causing a set of companies to face challenges in their business. For example, when energy prices went up in 2022, aluminium production was badly hit as electricity is a very important input into aluminium production. Tech changes reduced the profitability of Telcos is another example.

More importantly, however, long term investors like us take positions based on assumptions about the continued profit generating capabilities of the companies we own. When they can no longer generate the same levels of profit, and such degradation becomes apparently permanent, the investing community also re-rates the stock. This means that the stock is no longer priced for profit generation - it might just be priced for the assets the companies hold. This rerating could be very significant and lead to a permanent reduction in the valuation, and you and I as investors will stand to lose out.

This is what has happened to vast majority of the tech stocks in the past year or so - they have been re-rated from being measured on metrics such as Price-to-Sales, and at atmospheric multiples, to now down-to-earth multiples of Price-to-Earnings, which while being generous given the growth opportunities, still present a significant downward rerating of the valuations. Upward rerating is great for investors, the opposite not so much.

Example: GE

Dilution of Stock

When a company meets a temporary crisis in capital, where the business is neither insolvent today, nor has permanently degraded, but needs a dose of capital infusion to either keep going through the crisis, or to invest in the things needed to get things back to shape, then the company might choose to go to the markets for a capital raise - and depending on what terms are on offer, the company may dilute itself so much that investors from before the capital raise won’t see themselves above water on that investment.

Citibank, for enough, diluted itself enough to the tune of about 6x during the Great Financial Crisis, in order to stay solvent. The business survived, and has thrived since, but investor from before the crisis are yet to break even.

Examples: Citibank (2008), Carnival Corporation (2020)

Acquisition after a drop in price

Let’s say a stock drops in value, and we as long term investors are happy to hold as the business turns around, but a buyer comes along, puts out a really sweet offer and the board takes it? What happens then to you and I? We get locked into an exit on the stock at the price determined by the acquisition process and we may not like it.

In this case, our willingness to hold has been overwritten by the board, supported hopefully by some shareholders, and we are left bagholders.

Examples: Twitter, Yahoo

Regulatory / Societal Changes

The last category I wanted to talk about are cases of regulatory or societal changes that might leave an irrevocable mark on what the company can do, how much it can sell, how it can set its price and so and so forth. While in most cases, such actions are (a) predictable and (b) may not lead to the business entirely degrading, but in some extreme cases, might lead to either nationalisation, or semi-nationalisation of the business.

In recent years, ESG has caused many large investors to dump stocks that were considered non-ESG compliant. This is a case of Societal change.

Examples: Cigarette companies, AT&T breakup, Nationalisation of Banks in India (1969-1990)

Summary

As long term Coffee Can Investors, we should do our best to think about the companies we are buying and holding and whether or not there is a reasonable risk of these investments falling into one of the above categories. I don’t profess to have any specific expert knowledge in the field of loss-avoidance. All I can say is that companies that have weathered storms in the past are likely to outlive the next one, and buying healthy companies at sound valuations presents the best case for avoiding losses.

Can you think of other avenues losses I couldn’t think of?

This is a super recent example and an evolving situation, and might evoke emotional response based on how you are reading the story - that’s fine. While I am following this story will keen interest, there are much more examples from the past, on which much has been written about.

Geopolitical reasons.

Fintech crackdown by Chinese government led to hammering of Alibaba since Nov 2020.

Nationalisation is a big risk in certain countries. In others taxes could be so high as to amount to nationalisation. For example look at Harbour energy in UK. All of their profits have been offset by taxes imposed by the Government.