Kite Flying Season - in Delhi and in Whitehall

It’s kite flying season in Delhi.

Every year, as India’s Independence Day approaches on August 15th, rooftops across the city turn into launchpads for fierce, joyful aerial battles. In the weeks leading up to the big day, kids and adults alike gear up - shopping for the best manja (thread), scouting new kites, practising their moves, and yes, plotting petty revenge on neighbours who cut their line last year. (“That building took three kites from us - we’ve got to avenge that this year!”)

I was never the best flyer in my building team. But I was great at logistics. Making sure ढील देना (loosening of the reels), we had spare मांझा (kite-thread), taping torn पतंग (kites/sails), and general morale management - I had my place. Also helped that my neighbour, the team captain, liked me.

So why am I reminiscing about kite flying?

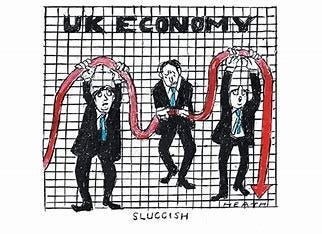

Because it’s in full swing here in the UK too - not in the skies, but in the press and policy circles. With budget season looming, every kind of policy proposal is being floated to see which ones catch the wind. One day it’s talk of cutting pension tax reliefs. Another day it’s capital gains hikes. Then it’s a wealth tax trial balloon. All of it is classic Westminster kite flying - lob a proposal into the air, gauge the outrage, and tweak accordingly (Kites 1, 2, 3).

The difference is: the kites in Delhi bring joy, competition, even hope. The ones here tend to bring anxiety, resentment, and confusion. I’d take my chances on a Delhi rooftop any day. Even if I lost a few kites, I’d still go home smiling. In the UK, everyone seems to lose.

🐘 The Three Beasts We Refuse to Tame

So what’s really going on?

Beyond the daily expenses of running the country, the UK government has three colossal, unrelenting obligations (ref):

State Pensions: £146 billion per year

NHS: £153 billion per year

Welfare Schemes: £195 billion per year

Together, they consume nearly half of all tax receipts, or about 16%–17% of GDP.

And they’re not shrinking. These are ever-growing beasts - politically protected, emotionally charged, and effectively untouchable. Over the years, through a combination of layered policymaking and unspoken political consensus, we’ve reached a quiet agreement: none of these can be meaningfully challenged or reformed.

Both major parties are complicit. The Opposition might posture while out of power, but once in government, they mirror the same reluctance to touch the sacred cows. The fiscal black hole deepens - but no one wants to name the cows, let alone move them.

So we’ve taken the next best (worst) option: tax the country more.

The UK already extracts roughly 35-36% of GDP in taxes. But that’s not enough. And instead of widening the base with consumption taxes or broad-based reforms, we’ve chosen to pile more weight on a narrow slice of the population.

Enter: the “broad shoulders.”

💼 The Myth of the Broad Shoulders

Enter the “broad shoulders” - the oft-invoked phrase for the supposedly well-off, roughly the top 4% of UK earners, those making over £100K a year.

We say they should “pay their fair share.” But here’s what that already looks like (ref):

They earn 25% of total income.

Yet they pay 48% of total income tax.

Still, they’re the first stop for every ludicrous revenue attack imposed:

The £100K childcare tax. (ref)

The infamous 60% marginal tax rate trap between £100K–£125K. (ref)

The pension contribution taper (even with recent reforms). (ref)

And for small business owners, the VAT cliff at £90K revenue. (ref)

All of these are essentially hidden taxes that punish ambition and growth - and in some cases, simply earning more.

We seem to forget: £100K isn’t the marker of plutocratic excess it once was. Especially in cities like London, it’s a comfortable, middle class income - not a signal of limitless financial firepower.

🚪The Exit and the Retreat

So how do the “broad shoulders” respond?

Two things - both rational.

They shrink their shoulders. Take less responsibility. Dial back on effort, ambition, output. Skip the promotion. Say no to the extra work. After all, what's the point?

They walk away. Physically. Move to friendlier tax jurisdictions1.

Neither is good for a country trying to grow.

We say we want a world-class tech sector, thriving biotech, global finance, creative excellence. We invest in great schools and world-class universities. But when that talent begins to pay off - we punish it. Relentlessly. And then act surprised when a key engine of growth sputters, or worse still, leaves.

🔄 Stagnation by Design

Here’s the part that rarely gets airtime: the real crisis is stagnation everywhere in the economy. The GDP isn’t budging. Median UK incomes, adjusted for global purchasing power, have barely moved in 25 years - and in dollar or euro terms, have actually declined. Those are the wounds we should be treating.

Instead of structural fixes to improve productivity, broaden the tax base, or recalibrate spending - we aim our fire at those who already contribute the most.

Worst still, the relentless on attack on the “broad shoulders” is backfiring - it reduces that section’s output, and in turn tax receipts and GDP produced. In turn, we tax some more. More exits. Rinse, repeat.

And to add to our miseries, the government’s willingness to let these kites fly, as well as the constant year-to-year tinkering with the tax code, means that we all live in uncertainty, which in itself leads to poor decision making involved. No one knows where we will land with the tax policy, so no one can plan for a future with it.

💥 Suicide by Tax Code

Everything currently on the table - wealth taxes, pension cuts, dividend changes - are marginal ideas - they will at best give you single digit billions - i.e. less than 1% of current tax take. They might raise headlines and even satiate some people baying for the blood of the “broad shoulders”, but they raise little money. What they do achieve, however, is to alienate and antagonise the group the system relies on to pay a good part of the tax take.

And make no mistake - this group is not “rich people.” They are just slightly well-off, but normal members of the society - SME business builders, knowledge workers, senior doctors, researchers, engineers, risk-takers, and yes, taxpayers - basically people who are somewhat useful to the society in general and the economy in particular.

If you wanted a front-row seat to a nation with world-class talent, world-class education, global language, ideal timezone, and centuries of compounding advantage - slowly choking itself with self-inflicted fiscal policies - Britain is it.

But if you’ve got broad shoulders, you might want to stay out of reach. Perhaps the best investment may simply come to be a one-way ticket out of the UK2.

When wealthy move to a different jurisdiction, filling that hole is a monstrous task. A typical £100K earner (and that’s the lowest end of the spectrum), pays about £30K-£35K in direct taxes alone, forget indirect taxes like Council taxes and VAT. At median income level, it will take about 10 people to fill that gap. That’s massive!

It seems I might have to backtrack on this - not yet, but might come along soon enough: