Book Review: What I Learned About Investing from Darwin by Pulak Prasad

A refreshingly interesting investment book

I recently completed reading the book “What I Learned About Investing from Darwin” by Pulak Prasad. A quick review and some snippets.

Pulak Prasad is the founder of Nalanda Capital, a Singapore-based investment firm that focuses on long-term investments in publicly listed Indian companies. Prior to founding Nalanda Capital in 2007, Prasad spent several years at Warburg Pincus working on their investments in India and Southeast Asia.

Prasad is not a trained Evolutionary Biologist and he admits as much. However, he has clearly studied it deeply enough to make very interesting inter-disciplinary parallels to the world of investing, demonstrating intellectual curiosity and innovative thinking.

The book deftly illustrates how principles such as natural selection, adaptation, and survival of the fittest can be applied to investing, highlighting the importance of adaptability and long-term thinking. Biology is among my least read subjects, and yet Prasad’s style of reading made the book eminently readable. His clear and engaging writing style makes intricate ideas relatable and easy to grasp, even for readers without a background in biology or finance.

Like many good books on investing, this book also emphasises psychological factors and human behavior in investing, specifically looking for patterns and biases that influence market movements with Prasad providing valuable lessons on maintaining discipline and avoiding common pitfalls. His personal anecdotes and case studies enrich the narrative, offering practical examples of how these principles can be implemented successfully.

Having said that, readers must be aware that this is not a book that is trying to draw scientific connections between the two fields or is drawing religious parallels. At best the connections and analogies make up for great reading and impresses upon generally good ideas in investing. The core message remains compelling: investors can learn a lot from natural species - adaptation, survival, evolution, compounding etc.

I present below a few snippets, organised by topics.

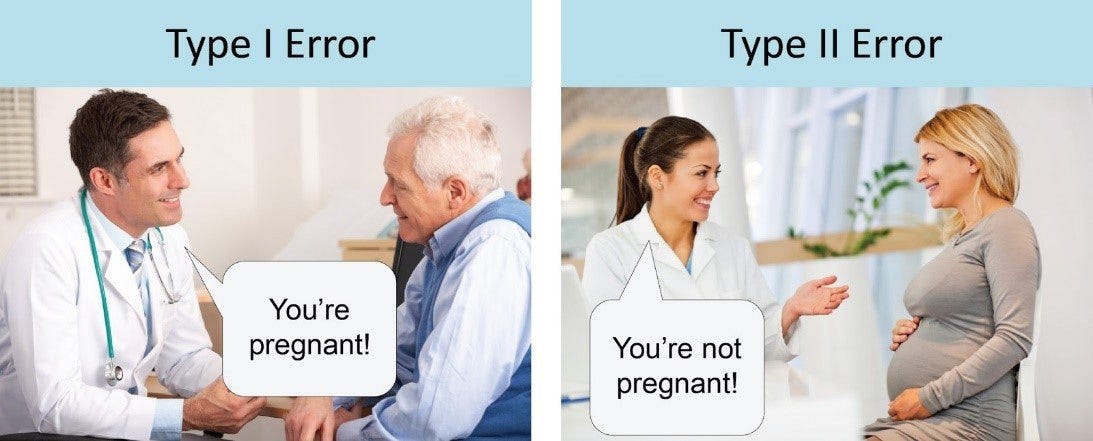

On Type 1 and Type 2 Mistakes

Almost everyone—and I say “almost” because this statement does not apply to my wife—makes mistakes. These errors fall into two broad categories: We do things we are not supposed to, and we don’t do things we are supposed to. For me, buying a hot fudge sundae at McDonald’s falls into the first category, and not keeping in regular touch with my school and college friends falls into the second.

As any statistician will tell you, the risk of these two errors is inversely related.2 Minimizing the risk of a type I error typically increases the risk of a type II error, and minimizing the risk of a type II error increases the risk of a type I error. Intuitively, this seems logical. Imagine an overly optimistic investor who sees an upside in almost every investment. This individual will make several type I errors by committing to bad investments but also will not miss out on the few good investments. On the other hand, an overly cautious investor who keeps finding reasons to reject every investment is likely to make very few bad investments but will lose out on some good investments.

Let’s now turn our attention to the predator. The predator, too, can make two types of error: It can commit itself to killing prey that turns out to be too dangerous or too large or too fast (type I error), or it can refrain from attacking prey that it could easily have killed (type II error).

Plants can choose to commit resources broadly to two areas: defending against attacks or growing. As with deer and cheetahs, any error that significantly compromises life or fitness for a plant can be categorized as a type I error. Since the lack of a proper defense may prove fatal to a plant, a type I error, or an error of commission, occurs when the plant does not devote resources to protecting itself. A type II error occurs when a plant directs energy toward preservation when it should have invested in growth. This error of omission may not kill the plant but may compromise its ability to grow and reproduce relative to its competitors. Ample evidence from nature suggests that plants avoid type I errors at the cost of committing more type II errors.

Plants, like animals, have found a way to their spectacular evolutionary success by focusing on reducing their errors of commission. In other words, like their animal counterparts, they avoid taking risks to their life and well-being at the cost of giving up some potentially juicy opportunities.

AND

Buffett has never explicitly explained this (at least I have never found an explanation), but this is what I think he means: Avoid big risks. Don’t make type I errors. Don’t commit to an investment in which the probability of losing money is higher than the probability of making money. Think about risk first, not return.

On natural selection

Dmitri Belyaev and Lyudmila Trut’s1 long-term experiment in Siberia has shown that selecting for tameness in wild silver foxes transforms them into a creature not unlike a pet dog over very few generations.

When the pups were about seven months old, the experimenters assigned them to one of three categories based on their tameness. Class III foxes were unfriendly toward the handlers and either ran away from them or were aggressive. Class II foxes behaved neutrally and displayed no emotional response toward the handlers. Class I foxes were the friendliest and seemed to want to engage with the handlers. Lyudmila and her team selected a few of the calmest Class I foxes for mating and repeated the experiment with the next generation of pups. By the third generation in 1962, Lyudmila noticed that some of the tamer foxes had started mating a few days earlier than usual and were producing slightly larger litters than wild foxes. Otherwise, there was no indication of any significant change. In April 1963, as Lyudmila approached the cages of the fourth generation of pups, she saw a male pup called Ember vigorously wagging his tail. This was precisely what a puppy would do. But no one had ever witnessed a silver fox—whether in a cage or the wild—wag its tail at a human. Ember wagged his tail at other humans, too.

AND

As an investor, would you not want to be in the position of selecting just one trait of a business but getting many high-quality attributes for “free”? As discussed earlier, this single trait should satisfy three criteria: it should be measurable, reject most businesses of poor quality, and select most high-quality businesses. Most, not necessarily all. We have seen that some factors like high-quality management, revenue growth, and margins do not serve the purpose well enough. At Nalanda, here is what we begin with while short-listing businesses: historical return on capital employed (ROCE). The first word first. Historical. I devote an entire chapter to this important and oft-ignored word, but for now I wanted to clarify that the ROCE number is what a business has delivered in the past.

Many investors prefer return on equity (ROE). I don’t. ROE is calculated after taxes and interest payments, and hence mixes operating performance with financing strategy and tax structure. As a business owner, I am much more concerned with the superior operating performance of a business. While taking on leverage (which will improve ROE but not ROCE) and “planning” for taxes may benefit a firm in the short to medium term, in my experience, success over the long term comes only by running great operations.

A company delivering high ROCE with modest revenue growth will generate excess cash. This is not an opinion—just a mathematical fact. For example, Company X growing its sales at 10 percent with ROCE of 25 percent can grow from zero cash to a cash balance of almost 18 percent of sales in five years (other assumptions: margin 15 percent, tax 30 percent). With an increasing cash cushion, X’s management team can choose to launch new products or target new geography. Even if the new business fails, X can recover given its ability to generate cash from its core business. Now let’s look at its competitor, Y, which is growing at the same rate (10 percent) with the same margin (15 percent) but with a lower ROCE of 12 percent. In five years, Y would have a negative cash balance of 3 percent of revenue. In other words, Y would have to borrow to grow at the same rate as X.

On using Macro

We have seen two problems with treating macroeconomic factors as critical proximate variables. First, we noticed that even big macro events (like the Asian financial crisis) are uncorrelated with longer-term stock price performance. Second, taking the example of the Indian tire industry, we concluded that using proximate economic data to assess industry and company performance is very hard, if not impossible. The third problem with using economic data is the most obvious of all. No one knows anything. Okay, that is exaggerating a bit. But only a bit. Since even expert economists are abysmal at forecasting the economy, why should we investors squander our time giving it any importance?

On Common Ancestry and not using DCF

Darwin proposed not one, not two, but three revolutionary theories in Origin: natural selection, sexual selection, and common ancestry. Let’s briefly see what these theories are and how he used history in all of them to arrive at his radical explanation of all organic life.

Natural selection requires three key ingredients.9 First, there needs to be random variation among the progeny of an organism. Note the word “random.” Variation does not seek any goal. Second, there needs to be differential fitness among these variants such that injurious variations get rejected and favorable ones are preserved. Last, the favorable traits must be heritable so that they are passed on to the next generation. Then, these three elements repeat ad infinitum over millions, even billions, of years. Resulting in a pangolin from a protozoan. In Darwin’s own words, “This preservation of favorable individual differences and variations, and the destruction of those which are injurious, I have called natural selection.”

Back to the lessons from Darwin. Like Darwin: • We interpret the present only in the context of history. • We see the same set of historical facts as everyone else. • We have no interest in forecasting the future. We study the history of a business to understand its financials, assess its strategies, gauge its competitive position, and finally assign value to it. So let’s take them one by one.

As per corporate finance theory, the value of a business is simply the sum of all its future cash flows discounted to the present time. This makes academic sense. It’s true mathematically. But as a practical way to invest, it borders on being nonsensical. Let’s understand why. There are two main requirements for building a DCF spreadsheet: the discount rate and the cash flow projection.

We have never done a DCF analysis and never will. However, I know many—if not most—investors and analysts do. Maybe they have figured out a method to look far into the future that eludes me.

On Convergence

When presented with a specific problem, the Caribbean anoles on different islands have evolved the same solutions, such as tail length, body length, and color. Amazingly, they have done it independently of one another. The anoles are a textbook example of evolutionary “convergence” wherein unrelated organisms in similar environments develop the same body form and adaptations independently.

I could go on and on to fill this book with examples of convergent evolution in the natural world. But scientists now agree that convergence is the rule, not an exception, in nature. This sentiment is best expressed by the most famous advocate of convergence, the Cambridge paleontologist Simon Conway Morris, who has written two books on the subject. He has explained convergence by saying, “Certainly it’s not the case that every Earth-like planet will have life let alone humanoids. But if you want a sophisticated plant, it will look awfully like a flower. If you want a fly, there are only a few ways you can do that. If you want to swim, like a shark, there are only a few ways you can do that. If you want to invent warm-bloodedness, like birds and mammals, there are only a few ways to do that.” Convergence in nature symbolizes a profound fact: There is a pattern to success and failure. What can the Caribbean anole, the crest-tailed marsupial mouse, and caffeine teach us about investing? Convergence in business symbolizes a profound fact: There is a pattern to success and failure.

Investing in companies is no different. Buying into a business means also buying into the industry of that business. For example, while I may think I am investing in a company that makes and sells sanitaryware, I am inheriting all the good and the bad of the sanitaryware industry. No company is an island. We can never ignore the kinds of businesses that surround it. One of our principles of convergence investing is that if the industry allows its companies to make money consistently, we love it; if not, we better have a perfect reason for spending even one minute analyzing a business like an airline. Life is too short.

On evolving companies

But in 1977, after a brief spell of rain in January, Daphne Major suffered a severe drought. Almost all the greenery disappeared from the island, and the only plants that survived the drought were cactus bushes. The finches fed on seeds of all sizes. The small and medium-sized seeds disappeared very soon, and the finches were then left with only large and hard seeds. But only the finches with larger beaks could break open these larger seeds; finches with small and medium-sized beaks could not open these seeds and so starved and perished.

In 1983, there was a very heavy rainfall because of El Niño, and the island became lush and green. Green vines covered even the cactus bushes. This changed vegetation had a significant impact two years later when drought struck again. This time, tiny seeds were abundant (produced by the vines of 1983), and large seeds became rare. As a result, the finches with large beaks found it hard to pick up the seeds, and a large proportion of the survivors of this drought were the small- beaked finches. Their offspring, as a result, also had smaller beaks. Natural selection and evolution were evident again, except that, unlike in 1977, the beaks had evolved to become smaller.

and

This realization has helped me formulate an investing principle that I call the Grant–Kurtén principle of investing (GKPI). It goes as follows:

When we find high-quality businesses that do not fundamentally alter their character over the long term, we should exploit the inevitable short-term fluctuations in their businesses for buying and not selling.

All investing models have downsides. In my opinion, no investment strategy is foolproof. If you know of one that is, please write a book on it (or better still, email me the magic formula). Our application of GKPI will have Kodak-like downsides, but in my experience, it works well most of the time. And that’s the best we can expect of any model.

High-quality businesses, too, seem to undergo many changes when measured over days or weeks or months but are much more stable when the period of measurement is years or decades. 3. Empirical data from the longevity of Fortune 500 businesses demonstrate the long- term resilience of exceptional businesses. About 40 to 45 percent of the Fortune 500 businesses of 1955 continued to be successful for the next sixty years.

If you found these snippets interesting, go pick up a copy and read through the whole thing - it is very much an enjoyable read.

As always, happy investing!

Conducted out of Novosibirisk

Do you know how he calculated the ROCE of 25% vs 12% example?