Microsoft 1999 and the AI Moment

Why history warns us about paying any price for the future

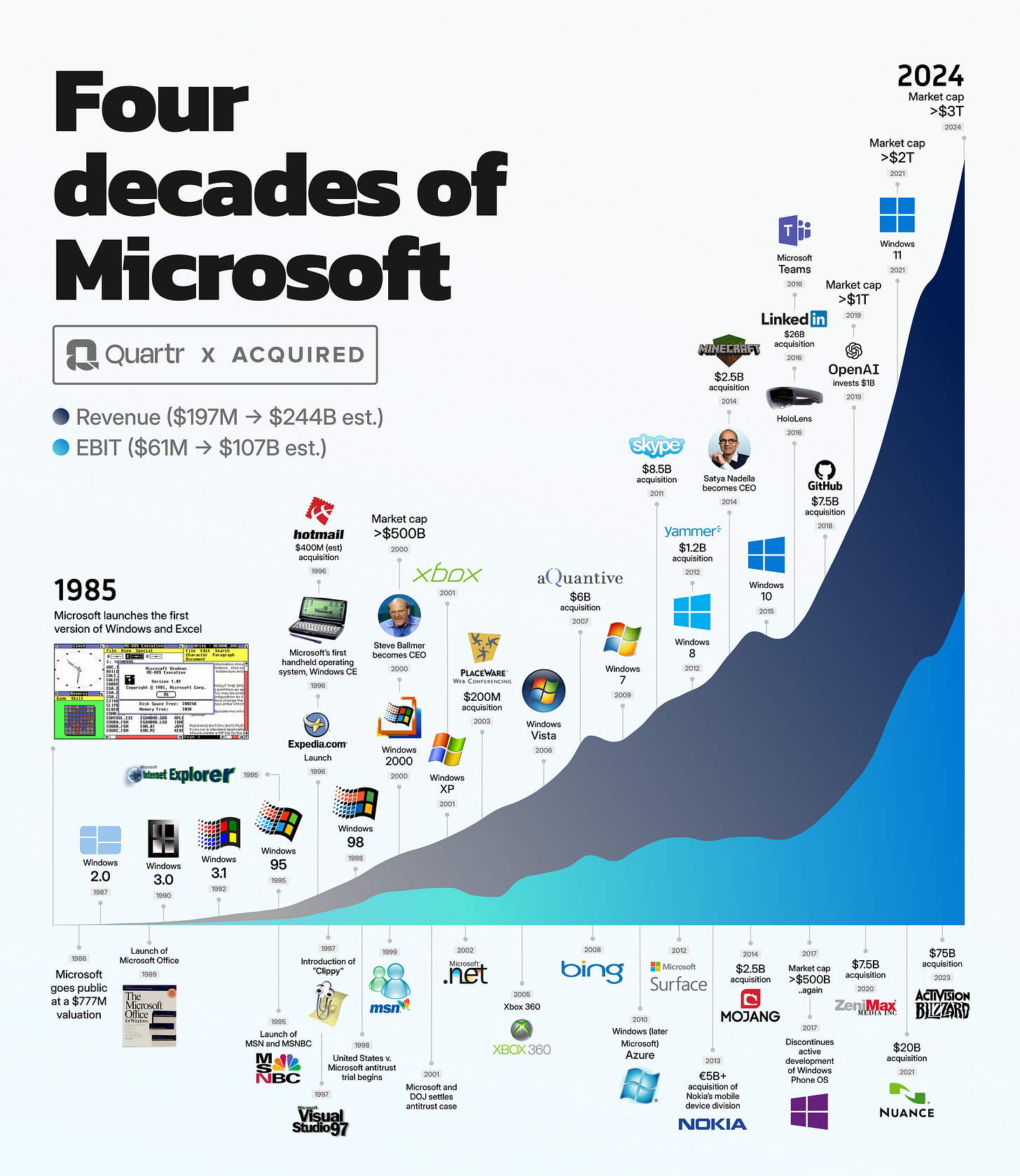

Microsoft is one of the rare, highly capitalised companies that has reached the very top of the market twice. Once during the dot-com era, and once again in modern times. In Dec 1999, Microsoft became the world’s most valuable company with a market capitalisation of roughly $616 billion, a distinction it would reclaim again in Jan 2024 and one it continues to contest today as one of the largest companies in the world.

And for good reason.

Over the past four decades, Microsoft has been a spectacular business. Its earnings per share grew from $0.14 in FY’95 to $13.64 in FY’25, representing a CAGR of 16.49%. Had you invested in Microsoft in 1996 and simply held on, that investment would have been a 60-bagger, compounding at 14.62% CAGR.

To put Microsoft into context, it belongs to a rare cohort of early technology giants that scaled to enormous size. Think Cisco, Intel, Oracle, and IBM. What stands out is that, decades later, Microsoft is the only company from that group that still occupies the very top tier of global market capitalisation. That survival is not accidental. It reflects durable moats, repeated reinvention, and an ability to endure shifts that wiped out many of its peers.

This history matters today because we once again find ourselves surrounded by companies touted as the inevitable future of the world and of stock market returns. NVIDIA, Tesla, SpaceX, OpenAI, and Meta. The stories are compelling. Yet history, from the Nifty Fifty to the dot-com era, reminds us that very few giants survive intact. At best, a handful do. Sometimes, only one.

The Business Story

Let us start with the business itself.

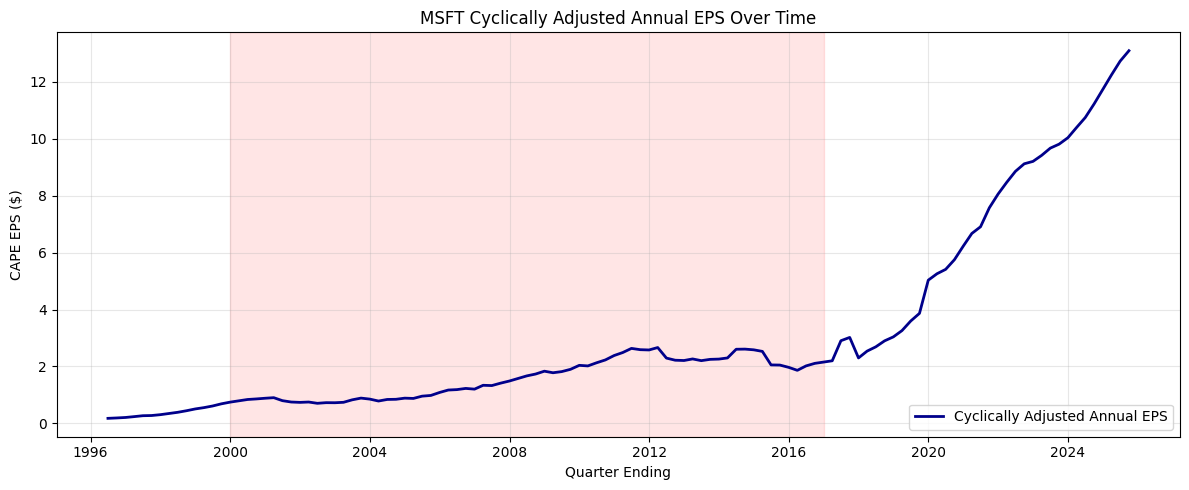

Split-adjusted, Microsoft earned roughly $0.24 per share in the mid-1990s. From there, earnings compounded impressively. Over the last forty years, EPS declined in only six years, often due to write-downs rather than underlying business weakness. More importantly, Microsoft reinvented itself multiple times.

It began as the dominant operating system and enterprise software company. It then struggled through the internet transition as Google emerged, followed by a difficult mobile chapter where Apple took the lead. Later, Microsoft found its footing again with cloud computing and now appears to be navigating the AI transition with far greater success.

One remarkable aspect of this journey is leadership continuity. Over its entire history, Microsoft has had only three CEOs: Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, and Satya Nadella. Gates defined the founder-CEO archetype. Ballmer presided over scale and profitability. Nadella engineered cultural and strategic renewal. Very few companies of Microsoft’s size have enjoyed such stable stewardship.

The Investor Journey

For investors, however, the story is far less linear.

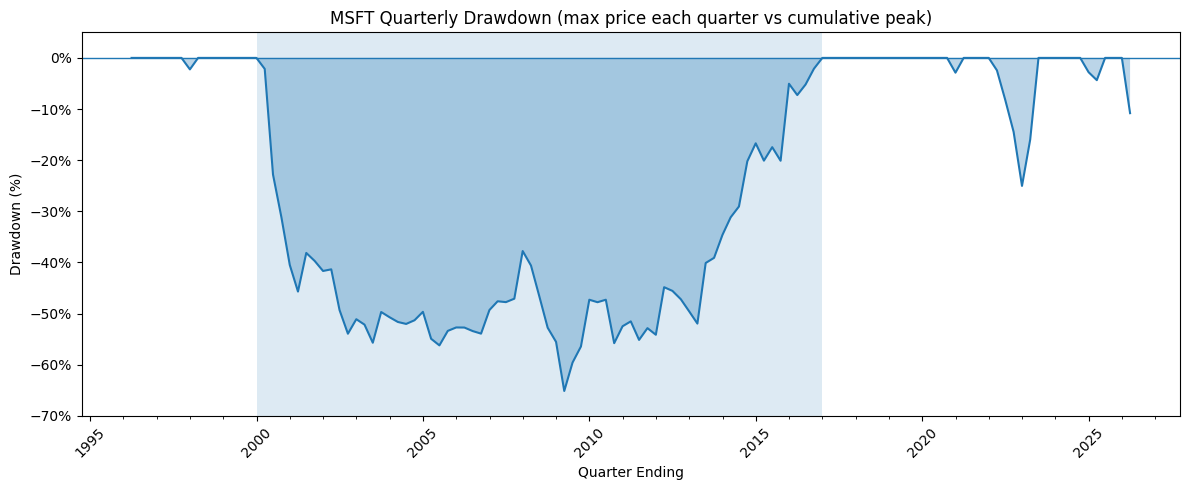

Microsoft was the unquestioned leader of the dot-com boom. By late 1999, its market capitalisation had reached nearly $600 billion, and it was a core holding in almost every institutional portfolio. The stock peaked on 1999-12-27 at $59.56 on a split-adjusted basis.

It would not surpass that price again until 2016-07-20!

That is over sixteen years just to break even. To recover opportunity cost, it likely took even longer. While the Japanese equity bubble is often cited as one of the worst investment experiences in history, prolonged drawdowns in marquee Western equities are far more common than many realise. And in choosing Microsoft, we are already looking at the survivor. Many of its contemporaries never recovered at all.

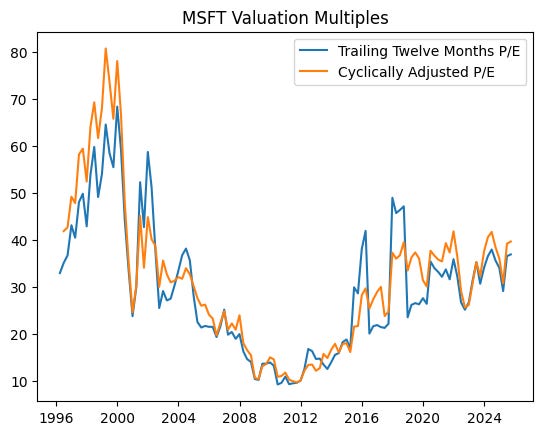

Valuation at the Peak

At the 1999 peak, Microsoft earned approximately $0.82 in trailing twelve-month EPS. Investors were willing to pay close to 70 times earnings. Given that the company earned EPS of $0.90 in the next 12 months, that’s 66x forward earnings!

These were extraordinary valuations.

At that price, it took the company roughly 22.5 years to earn back the $59.56 paid in December 1999. Business growth alone was not enough to deliver acceptable investor returns over long periods when starting valuations were extreme.

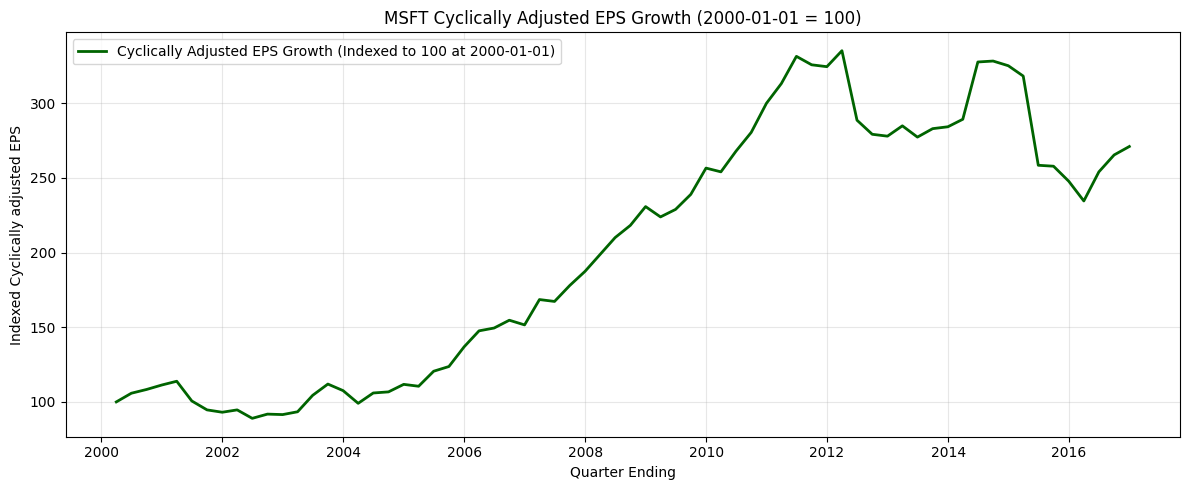

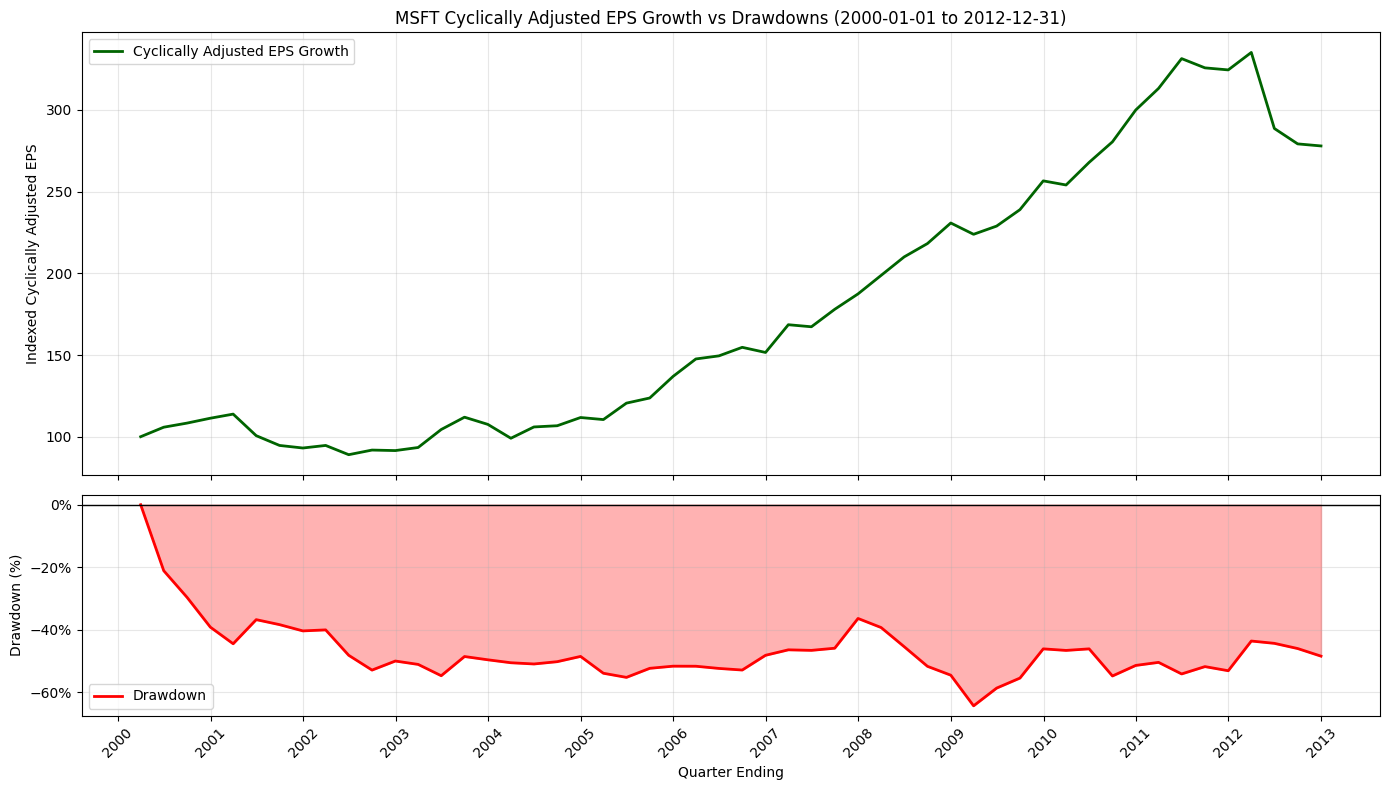

ps: As a methodological note, to smooth earnings volatility caused by occasional write-downs, I have used cyclically adjusted earnings. The adjustment window is two years, long enough to reduce noise while still capturing business dynamism.

When the Business Thrives but Investors Suffer

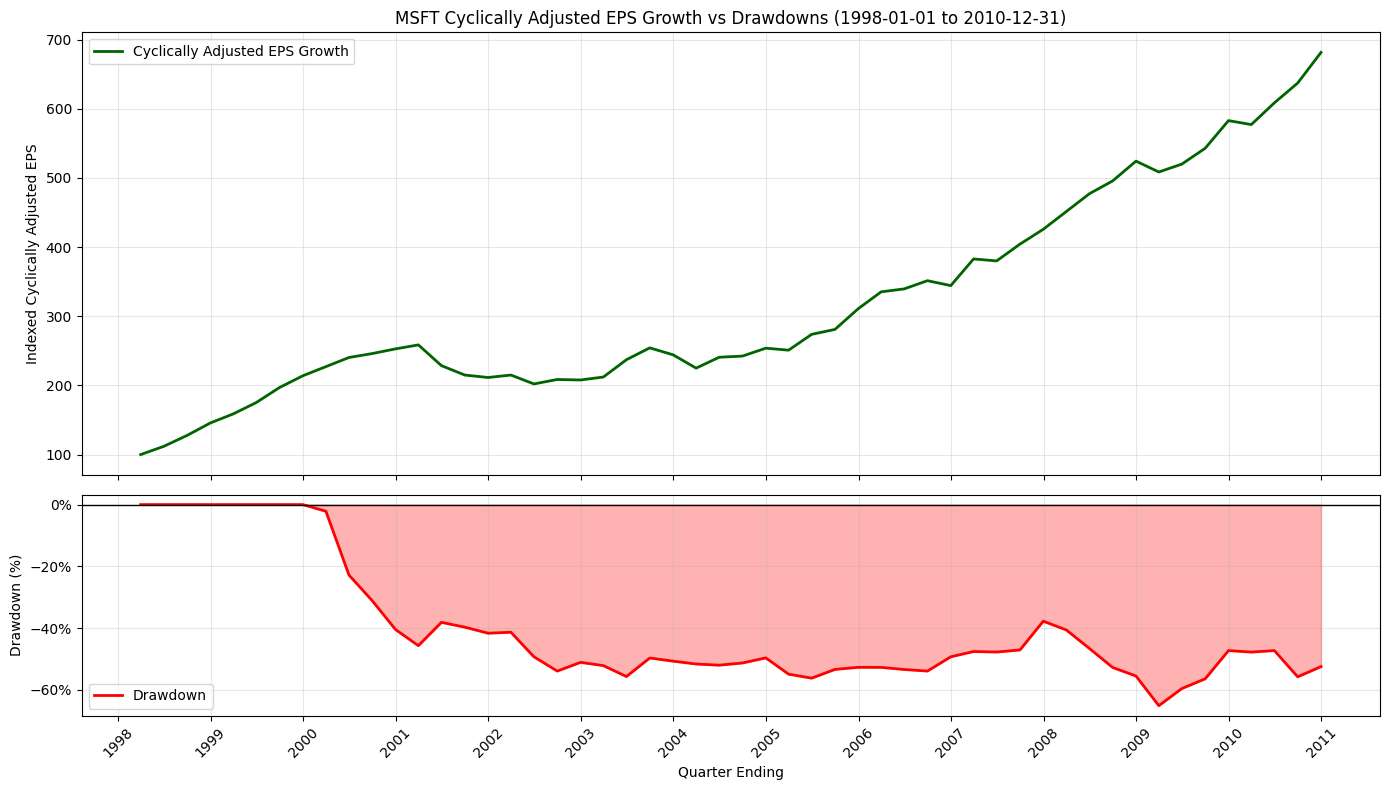

During the extended drawdown period, the business continued to perform well. Earnings roughly tripled, cash flows remained strong, and the franchise strengthened. Meanwhile, valuation multiples compressed dramatically. From roughly 66x earnings at the peak, valuations fell to nearly 10x at the bottom before stabilising around 14 to 15x when the stock finally broke even.

Viewed side by side, the contrast is striking. Earnings compounded steadily while investors experienced deep and persistent drawdowns. For over sixty consecutive quarters, shareholders were underwater even as the business itself grew.

One might argue that only investors unlucky enough to buy at the exact peak suffered. But shifting the entry point earlier does not materially change the picture.

Buying one or even two years earlier still resulted in extended periods of drawdown. Timing mattered far more than business quality alone.

What If You Used a Holding Period Strategy?

Perhaps, instead of buy and hold, you might argue for a disciplined strategy. Hold for a fixed number of years, reassess, and move on if returns disappoint.

Fair enough.

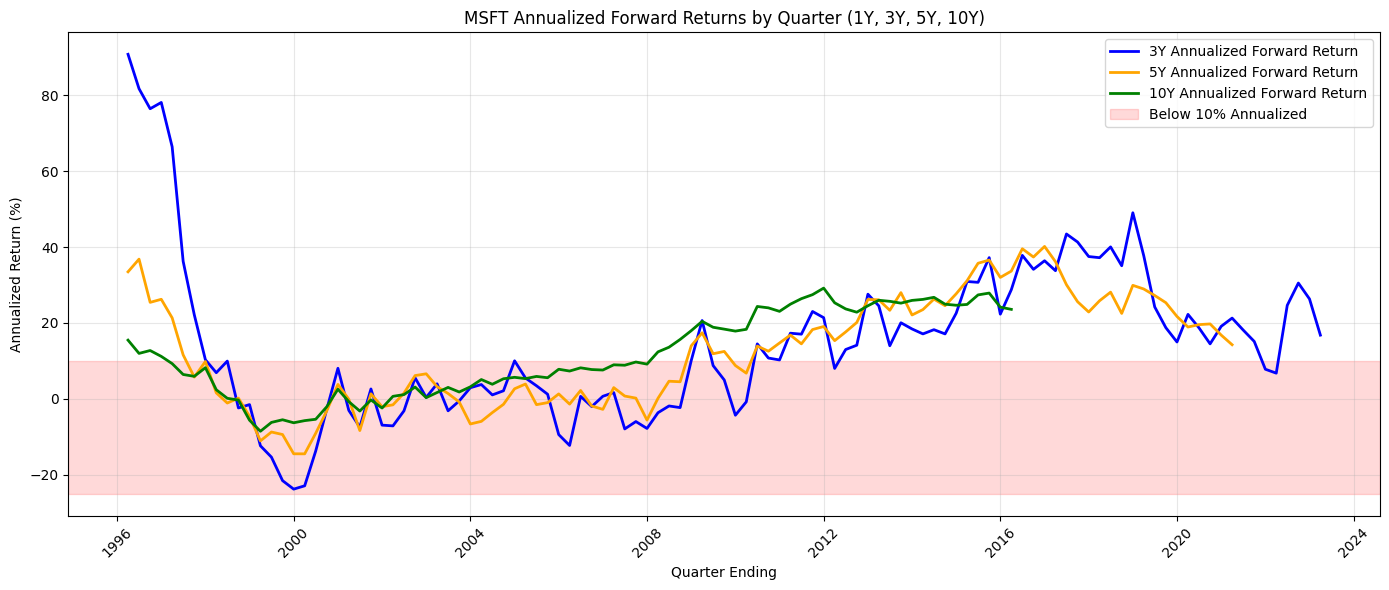

Here is what forward returns looked like for Microsoft investors, measured over rolling 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year periods. The shaded region highlights annualised returns below 10 percent.

For long stretches, even patient investors earned less than 10 percent annually. In some windows, returns were far worse. This was not due to a broken business. It was the consequence of starting valuations that left no margin for error.

Closing Thoughts

The broader lesson is not that one should avoid great companies. On the contrary, identifying businesses with durable moats, strong balance sheets, resilient cash flows, and stable leadership is essential.

But valuation still matters enormously.

AI will almost certainly change the world, just as personal computing, the internet, mobile, and cloud computing did before it. Yet most dominant players from those earlier revolutions faded away. Even one of the few survivors, Microsoft, delivered a decade and a half of pain for investors who entered at the wrong price.

This time may be different. Or it may not be.

Tread carefully.

On that note, happy investing.

Disclaimer: I am not your financial advisor and bear no fiduciary responsibility. This post is for educational and entertainment purposes only. Do your own due diligence before investing. I may hold or enter into positions in the securities mentioned above. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any security.