Berkshire 2024 Review

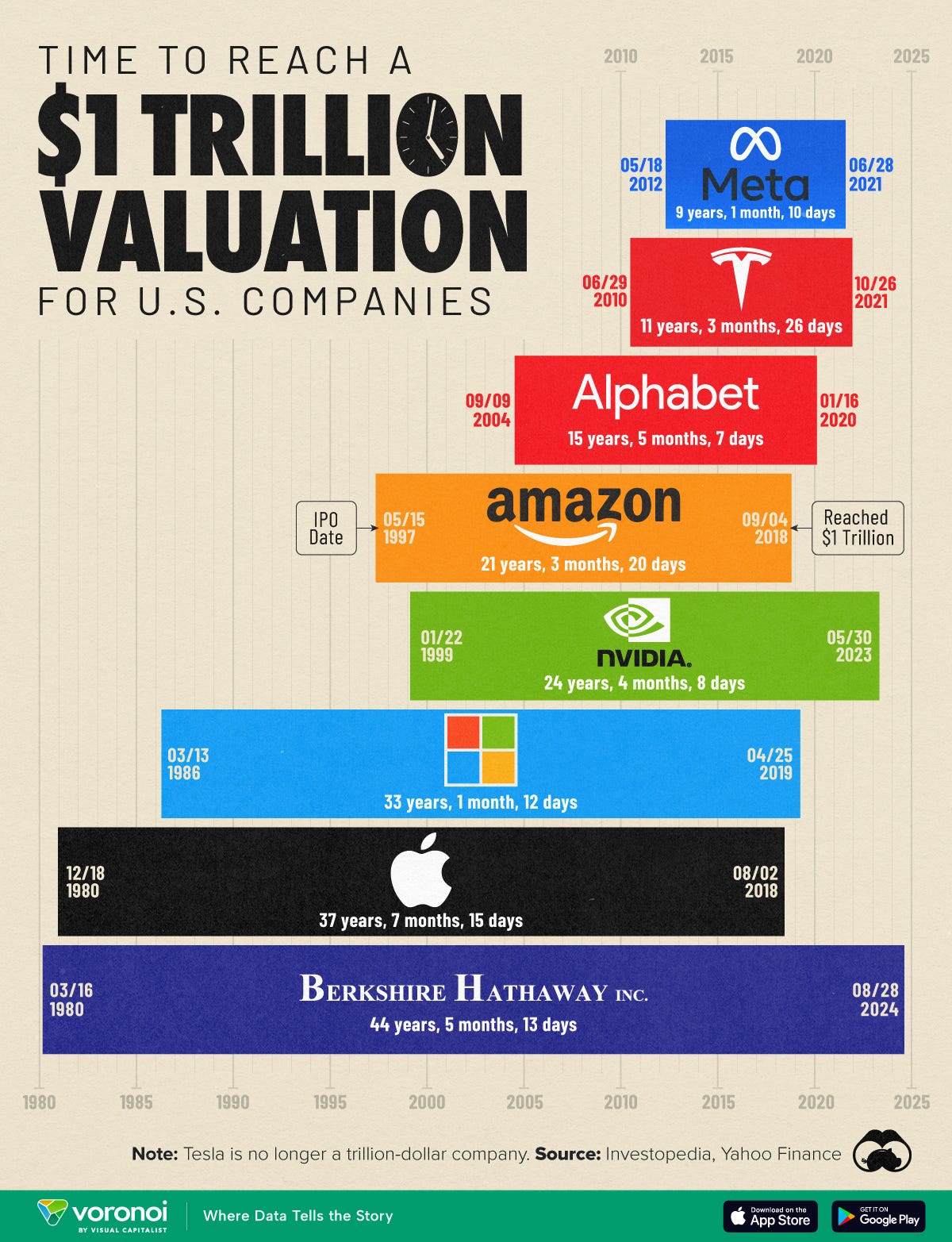

Crossed the $1Tn market cap, the slow and steady way

If your financial goal is to find a company that will make you rich slowly but steadily, while taking its fiduciary responsibilities seriously and doing so at an extremely low cost, then stop your search—I have the answer.

And no, it is not Apple, NVDA, Google, or any other tech giant. These companies are innovators, disruptors, and providers of essential goods and services that help build businesses. However, none of them act as fiduciaries.

Only a handful of companies operate in the business of money management. While firms like BlackRock and various banks manage money for others, as an investor, you don’t get to partake in their successful management of funds.

The marvel of the company I’m writing about today is that it came into existence almost by accident, and no one has attempted to replicate its structure since. Make no mistake—there is no shortage of people willing to manage money on your behalf, but no one does so as a publicly listed corporation without charging a fund management fee (read "2 & 20").

So, let me once again pay my annual homage to the one company I admire above all—Berkshire Hathaway.

At the time of writing, it is my largest direct holding, now accounting for more than 27% of my coffee can portfolio. Last year, when I wrote a similar post, it was just 17%. Over the past year, I have entrusted an even larger portion of my family’s wealth to Berkshire.

Berkshire released its 2024 annual report over the weekend, and true to form, Warren Buffett wrote an extremely short letter. As always, he maintained his signature sense of humor while expressing deep gratitude for America. I’m going to highlight the parts that resonated with me most, but for those interested, I highly recommend reading the entire letter.

Warren, being candid as ever

During the 2019-23 period, I have used the words 'mistake' or 'error' 16 times in my letters to you. Many other huge companies have never used either word over that span. Amazon, I should acknowledge, made some brutally candid observations in its 2021 letter. Elsewhere, it has generally been happy talk and pictures.

On Pete Liegl and compensation

Then we arrived at the other point that needed clarity. I asked Pete what his compensation should be, adding that whatever he said, I would accept. (This, I should add, is not an approach I recommend for general use.)

Pete paused as his wife, daughter, and I leaned forward. Then he surprised us: 'Well, I looked at Berkshire’s proxy statement, and I wouldn’t want to make more than my boss, so pay me $100,000 per year.' After I picked myself off the floor, Pete added: 'But we will earn X (he named a number) this year, and I would like an annual bonus of 10% of any earnings above what the company is now delivering.' I replied: 'OK, Pete, but if Forest River makes any significant acquisitions, we will make an appropriate adjustment for the additional capital thus employed.' I didn’t define 'appropriate' or 'significant,' but those vague terms never caused a problem.

This highlights an often understated virtue—basic trust and good-faith negotiations. From my own experience, some of my most financially rewarding partnerships were formed without a contract or fine print. Simple handshakes worked wonders. If you can find people you can trust like that, life can be wonderful.

On the futility of looking at education when recruiting leaders:

One further point in our CEO selections: I never look at where a candidate has gone to school. Never!

On Taxes

I genuinely dislike paying taxes. However, one lesson I can take from Warren is his willingness to celebrate the taxes Berkshire pays—now a record for corporate America. (From what I’ve heard, he also optimizes for taxes—he’s not that charitable—but with age, he has accepted it a lot more.)

Fast forward 60 years and imagine the surprise at the Treasury when that same company – still operating under the name of Berkshire Hathaway – paid far more in corporate income tax than the U.S. government had ever received from any company – even the American tech titans that commanded market values in the trillions.

To be precise, Berkshire last year made four payments to the IRS that totaled $26.8 billion. That’s about 5% of what all of corporate America paid. (In addition, we paid sizable amounts for income taxes to foreign governments and to 44 states.)

And, of course, some folksy humor to go with it:

If Berkshire had sent the Treasury a $1 million check every 20 minutes throughout all of 2024 – visualize 366 days and nights because 2024 was a leap year – we still would have owed the federal government a significant sum at year-end. Indeed, it would be well into January before the Treasury would tell us that we could take a short breather, get some sleep, and prepare for our 2025 tax payments.

On Japan

This section highlights why Berkshire’s management tends to get capital allocation right. Discussing recent investments in Japan:

At year-end, Berkshire’s aggregate cost (in dollars) was $13.8 billion, and the market value of our holdings totaled $23.5 billion.

We like the current math of our yen-balanced strategy as well. As I write this, the annual dividend income expected from the Japanese investments in 2025 will total about $812 million, and the interest cost of our yen-denominated debt will be about $135 million.

Without putting down a penny from their own pockets, they are now collecting $677 million in annual dividends—roughly 5% of the money put at risk. Notably, the investments were funded by long-dated Japanese bonds with a fixed interest rate. If you find other companies that can generate $5 billion in gains and $677 million per year in dividends almost purely out of will, let me know—I’d consider investing. But here’s the kicker—this trade adds no leverage for Berkshire. The $13.8 billion of capital at risk represents just 4.15% of its cash reserves. Even if every single Japanese company in this investment goes bust, Berkshire would still stand firm. When applying leverage, you must know how to avoid financial ruin.

(Short) Business Review

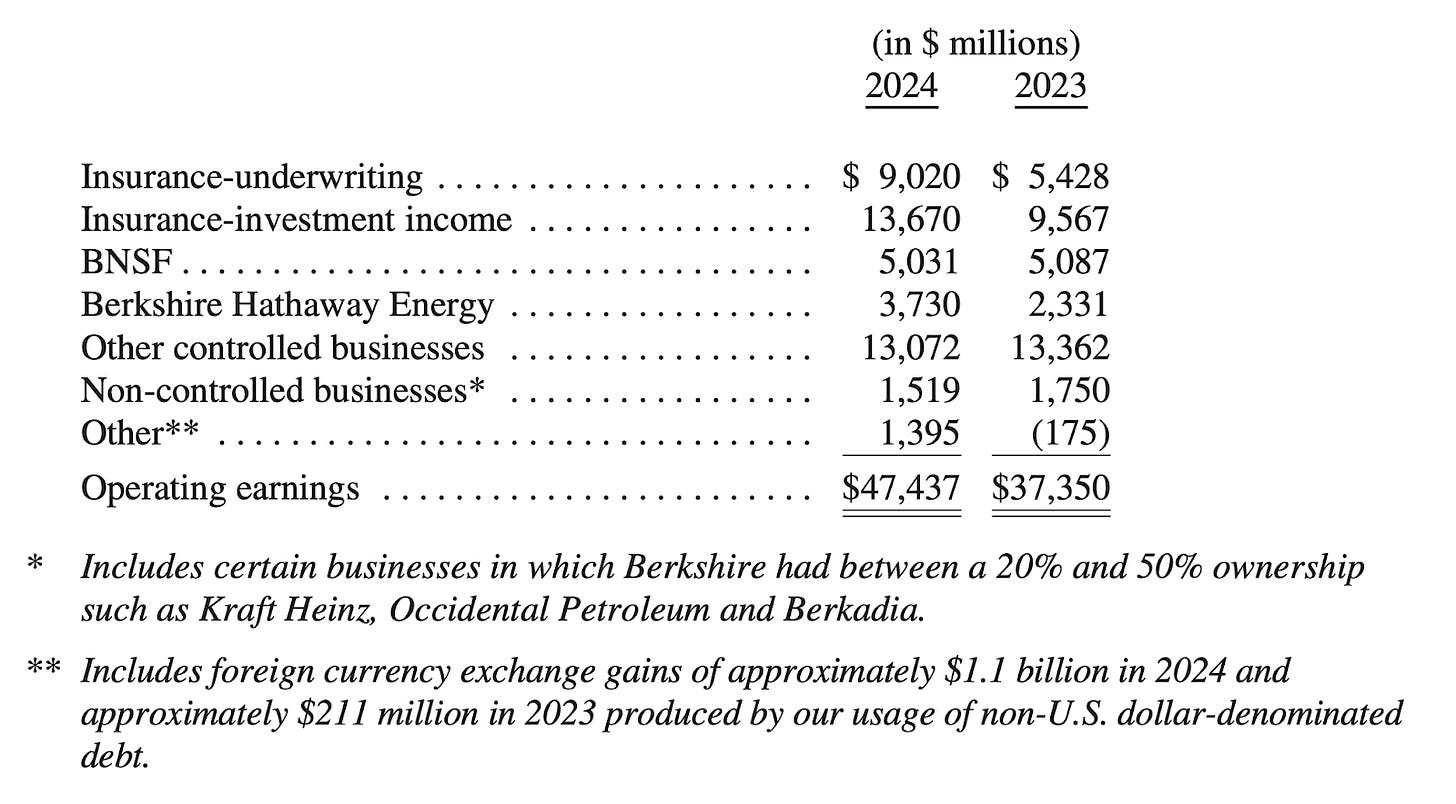

Now, let’s do a quick review of Berkshire’s business and valuation.

The company earned $47.4 billion in operating income (excluding any investment income). As of December 31, its market cap was around $974 billion (~$1.033 trillion today), of which $334 billion was in cold hard cash and another $272 billion in marketable securities. The remaining $368 billion represented the valuation of its operating businesses.

These operating businesses generated $47.4 billion in earnings, implying a 7.8x P/E ratio. That figure stood at 13x last year. The market is now valuing Berkshire’s operating businesses even lower than before. Unless there’s a massive mathematical error or Berkshire turns out to be a front for a gigantic fraud, this is an incredibly attractive investment opportunity.

I’ll take more of it. Thank you.

As always, happy investing!

Disclaimer: I am not your financial advisor and bear no fiduciary responsibility. This post is only for educational and entertainment purposes. Do your own due diligence before investing in any securities.

Why is the market valuing the operating businesses even lower?? Good time to buy I guess..